Years later, José and his family still feel the pain of their past. In May 2018, federal agents took José from his father’s arms at the southern border. He was one of thousands of migrant children affected by a policy under former President Trump’s immigration agenda.

At just five years old, José was placed with a foster family in Michigan. The Times previously reported on his experience. Today, José is in sixth grade in Houston, living with his parents again. He is thriving academically, plays guitar in the school band, and has a growing passion for soccer. His English teacher, Ms. Keller, recently encouraged him, stating in a note, “You possess all the qualities to take you very far in life.”

Despite his achievements, José carries the weight of his experiences. “I don’t trust anybody,” he said in an interview last week, “I just trust my mom and dad.” The memories of his separation remain vivid. “I think about it,” he admitted. “I just don’t tell anyone about it.”

His family’s immigration status is still uncertain. They remain undocumented as Trump campaigns for another presidential term, promising to reinstate strict immigration measures. This looming threat has left a lasting impact on families affected by the previous separation policy.

Trump remarked on CNN last year, “When you have that policy, people don’t come. If the family hears that they’re going to be separated, they love their family. They don’t come.”

Despite federal courts declaring the family separation policy unconstitutional, concerns linger. Trump, who has vowed mass deportations, recently avoided direct questions about potentially reinstating family separation policies. Mr. Vance echoed these sentiments during a visit to the southern border, suggesting that “every time somebody is arrested for a crime, that’s family separation,” while stressing the need to enforce laws.

Vice President Kamala Harris, while campaigning for the presidency, has projected a tougher approach on immigration than President Biden. However, she has indicated that some measures, including family separation, should not return. During a recent event in Doral, Florida, she showcased children who had been reunited with their families. One of them, a teenager named Billy, expressed his fears, saying, “I go to therapists, but I still have the fear of Trump being re-elected and the same thing happening.”

The zero-tolerance policy implemented in 2018 charged adults with illegally entering the U.S., resulting in their imprisonment. Children, even infants, were sent to shelters or foster homes. The aim was to deter family migration to the U.S., which had surged at the time.

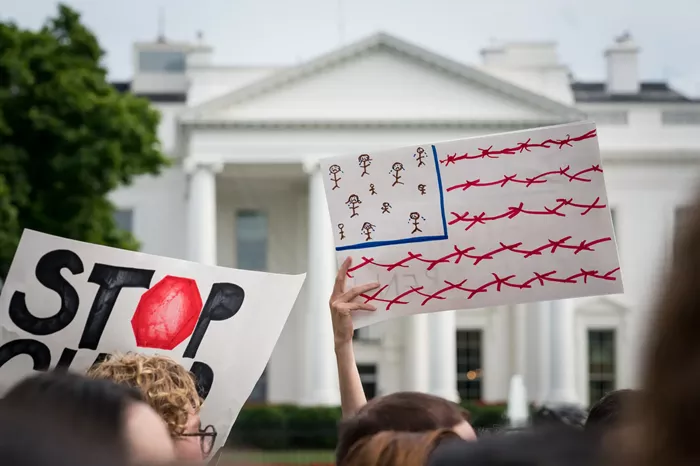

However, public outcry arose when images and audio recordings of crying children surfaced. This led to widespread condemnation from various groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, Pope Francis, and former First Lady Laura Bush. In response to the backlash, Trump suspended the policy in June 2018 after a federal judge ordered the reunification of families.

Reuniting families proved complicated due to inadequate record-keeping by authorities. In 2021, the Biden administration set up a task force to help reunite families, working with nonprofits to find deported parents. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) estimated that up to 1,000 families may still be separated.

Lee Gelernt, the lead counsel for the ACLU, stated, “I doubt very much that most people realize how many little children are growing up without their parents or understand the continuing trauma experienced even by those children lucky enough to have been reunited.”

Under a recent settlement, deported parents can legally join their children in the U.S. and obtain temporary work permits. The families are also eligible for mental health and legal services and many are applying for asylum, which could lead to green cards.

Janice Barbee, who fostered José, vividly remembers picking him up at the airport in May 2018. “All I could see was fear and confusion in those beautiful brown eyes,” she recalled. He did not cry but would not hold her hand either. “In that moment, I wondered if he would ever heal from this unimaginable trauma of separation.”

Janice read him bedtime stories and her husband encouraged his love for soccer. They took him on family outings. Even as José began to feel more at home, he clung to two drawings: one of his family and another of his father wearing a cap. He kept them close, tucking them under his pillow at night.

Once, José had a meltdown while holding the family drawing. “He held onto it as he cried and wailed on my kitchen floor,” Janice recounted. “In that moment, I wondered if he would ever heal from this unimaginable trauma of separation.”

José’s father was deeply concerned that his son might be adopted. He turned down an offer from U.S. authorities to return to Honduras, insisting he would not leave José behind. Father and son were finally reunited in October 2018, five months after they were separated.

“Why were you sent to jail? What did you do wrong?” José asked his father upon their reunion. His father noted that José cried easily and suffered from nightmares. In 2019, José’s mother and younger siblings joined them in the U.S. The family fled Honduras after gang members shot and injured José’s father for refusing to pay extortion.

In a September 2021 interview, José was a cheerful and chatty third-grader. He recalled, “My dad stayed in prison a year.” He explained he had been separated from his parents twice—once when his father was jailed and again when his mother was hospitalized. However, he expressed happiness when his mother returned home with his baby sister.

José’s parents agreed to share their story on the condition that their identities remain confidential. Like many separated families, they are fearful and distrustful of authorities, which has prevented them from accessing available support services. As a result, they have missed out on benefits and protections under the recent settlement and remain at risk of deportation.

With the presidential election approaching, José’s parents are hesitant to take any steps that could expose them to a future administration’s immigration policies. Recently, José mentioned that he is aware of the election and knows the names of the candidates. When asked how they differ, he said, “Trump doesn’t like the immigrants.”

When asked who he hoped would win, he replied, “Everybody has a different opinion. I can’t vote.”

Returning to his studies, José proudly shared that he recently scored the highest in his class on an English assessment and had been named sixth-grade student of the month.

Related topics:

- Farm Communities Divided Over Proposed Immigration Raids

- DOJ Discovers Potential Future Embarrassment, Not Antitrust Violations Against Visa

- US Issues Warning: Visa Restrictions for Those Threatening Ghana’s Democracy